Above and Beyond

Excerpted from the Spring 2002 issue of Saint Louis University Hospital’s Emergency Perspectives. Reprinted with permission.

Excerpted from the Spring 2002 issue of Saint Louis University Hospital’s Emergency Perspectives. Reprinted with permission.

Many EMS professionals and firefighters can’t seem to get enough of helping people. Even as they spend their working hours providing medical treatment to the sick or rescuing those in peril, they await the call that will take them somewhere different, unknown, challenging, exciting – all in the service of people they don’t know.

There are hundreds of emergency workers who go above and beyond their regular duties by volunteering during times when the worst that could happen becomes reality. We talked with just a few of them to learn about their experiences and to discover what drives them toward danger while others retreat.

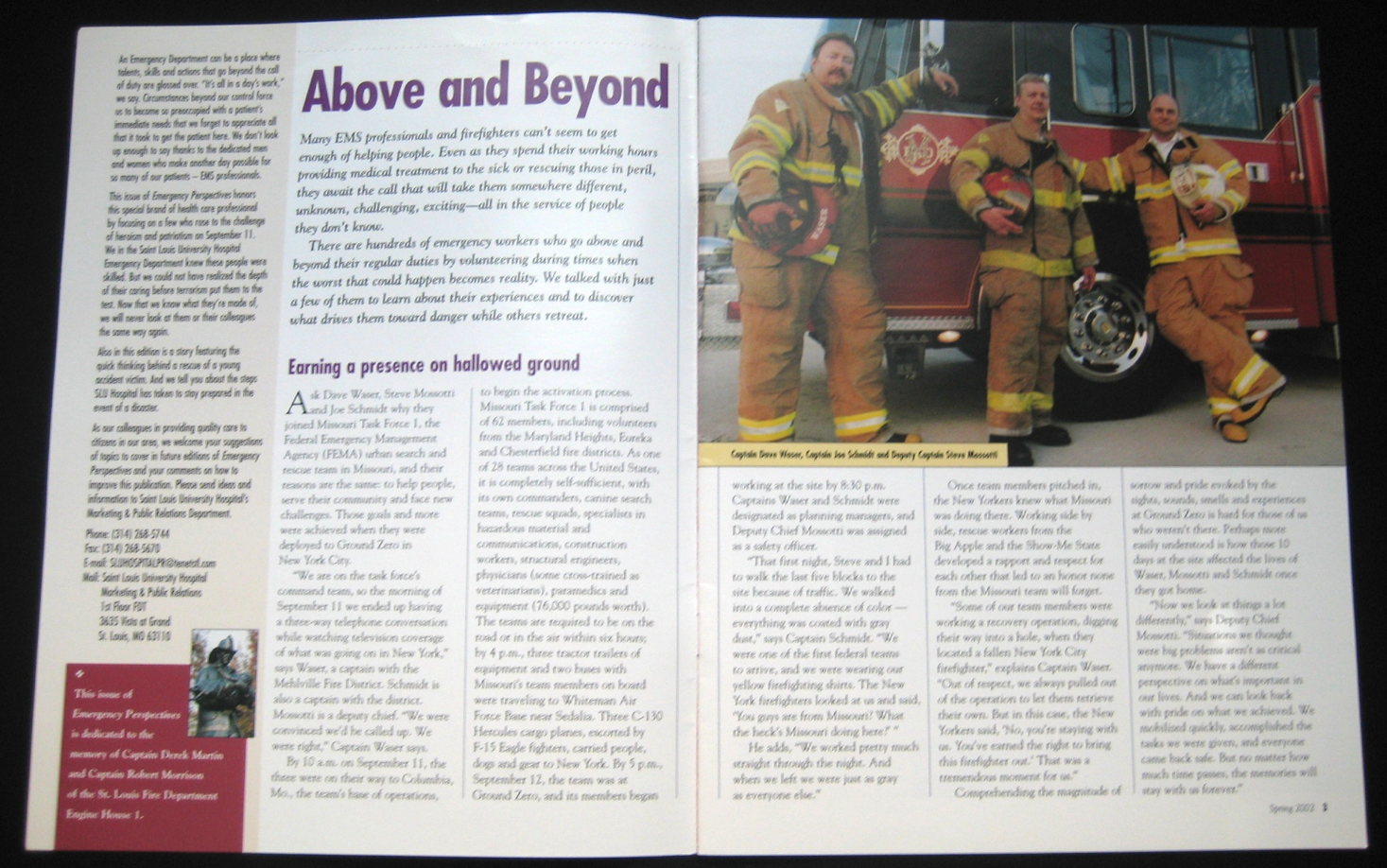

Earning a presence on hallowed groundAsk Dave Waser, Steve Mossotti and Joe Schmidt why they joined Missouri Task Force 1, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) urban search and rescue team in Missouri, and their reasons are the same: to help people, serve their community and face new challenges. Those goals and more were achieved when they were deployed to Ground Zero in New York City.

“We are on the task force’s command team, so the morning of September 11 we ended up having a three-way telephone conversation of what was going on in New York,” says Waser, a captain with the Mehlville Fire District. Schmidt is also a captain with the district. Mossotti is a deputy chief. “We were convinced we’d be called up. We were right,” Captain Waser says.

By 10 a.m. on September 11, the three were on their way to Columbia, Mo., the team’s base of operations, to begin the activation process. Missouri Task Force 1 is comprised of 62 members, including volunteers from the Maryland Heights, Eureka and Chesterfield fire districts. As one of 28 teams across the United States, it is completely self-sufficient, with its own commanders, canine search teams, rescue squads, specialists in hazardous material and communications, construction workers, structural engineers, physicians (some cross-trained as veterinarians), paramedics and equipment (76,000 pounds worth). The teams are required to be on the road or in the air within six hours; by 4 p.m., three tractor trailers of equipment and two buses with Missouri’s team members on board were traveling to Whiteman Air Force Base near Sedalia. Three C-130 Hercules cargo planes, escorted by F-15 Eagle fighters, carried people, dogs and gear to New York. By 5 p.m., September 12, the team was at Ground Zero, and its members began working at the site by 8:30 p.m. Captains Waser and Schmidt were designated as planning managers, and Deputy Chief Mossotti was assigned as safety officer.

“That first night, Steve and I had to walk the last five blocks to the site because of traffic. We walked into a complete absence of color – everything was coated with gray dust,” says Captain Schmidt. “We were one of the first federal teams to arrive, and we were wearing our yellow firefighting shirts. The New York firefighters looked at us and said, ‘You guys are from Missouri? What the heck’s Missouri doing here?'”

He adds, “We worked pretty much straight through the night. And when we left we were just as gray as everyone else.”

Once team members pitched in, the New Yorkers knew what Missouri was doing there. Working side by side, rescue workers from the Big Apple and the Show-Me State developed a rapport and respect for each other that led to an honor none from the Missouri team will forget.

“Some of our team members were working a recovery operation, digging their way into a hole, when they located a fallen New York City firefighter,” explains Captain Waser. “Out of respect, we always pulled out of the operation to let them retrieve their own. But in this case, the New Yorkers said, ‘No, you’re staying with us. You’ve earned the right to bring this firefighter out.’ That was a tremendous moment for us.”

Comprehending the magnitude of sorrow and pride evoked by the sights, sounds, smells and experiences at Ground Zero is hard for those of us who weren’t there. Perhaps more easily understood is how those 10 days at the site affected the lives of Waser, Mossotti and Schmidt once the got home.

“Now we look at things a lot differently,” says Deputy Chief Mossotti. “Situations we thought were big problems aren’t as critical anymore. We have a different perspective on what’s important in our lives. And we can look back with pride on what we achieved. We mobilized quickly, accomplished the tasks we were given, and everyone came back safe. But no matter how much time passes, the memories will stay with us forever.”

From Ground Zero to the OlympicsGary Christmann began his career as a St. Louis paramedic, but found he had an interest in emergency management. He started taking courses on the subject in 1995 and volunteered with the St. Louis Emergency Management Agency as a HAM radio operator. Now working full time for the agency as a technician specialist, Christmann has taken his interest a step further by volunteering with the Greater St. Louis Bi-State Disaster Medical Assistance Team, known as MO-1 DMAT. the team is one of 60 throughout the United States that sends medical professionals and other vital personnel to disaster sites. Christmann began as a paramedic with MO-1 DMAT and then became a communications specialist because of his radio experience. He now serves as the unit’s deputy commander.

“I wanted a way to broaden my disaster response capabilities. The medical assistance team was definitely a way for me to do that,” explains Christmann.

Christmann and other MO-1 DMAT members’ experience broadened quickly with the advent of the September 11 terrorist attacks. Like the FEMA Missouri Task Force 1 team, Ground Zero was MO-1 DMAT’s first disaster deployment.

“I was attending a terrorism course at Fort McCullum in Alabama when word came of the terrorist attacks,” says Christmann. “I wasn’t able to get back to St. Louis until September 13, but then I immediately left for New York.”

In addition to Christmann, MO-1 DMAT sent nurses, physicians and communications officers to New York. “I worked in communications, helping different teams such as disaster medical, disaster mortuary and disaster vets with radios, cell phones, Nextels and computer networking,” says Christmann. “I volunteered to stay an extra week, so I was there for three weeks. There are things about the experience I’d like to forget. My good memories, though, are of how people pulled together and how well-organized and responsive our government teams were.”

Months later, Christmann was assigned to the Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City, an exciting, uplifting event for the country that became a serious security challenge after September 11. Although Christmann, as chief of operations over communications, was continually busy, other DMAT team members remained idle.

“It was a large scale operation like New York, but the majority of team members spent their time waiting, ready in case anything happened. To our relief, nothing did,” says Christmann.

Rather than dampening his enthusiasm, Christmann’s experiences have increased his commitment to MO-1 DMAT. “I learned a lot in New York, and I’m using that knowledge to better prepare St. Louis and MO-1 DMAT for any large-scale emergency situations – natural or man-made,” he says.

Canine search and rescue: another way of helpingA quick rundown of Debbie Ross’ resume shows her lifelong commitment to helping people. First she was a teacher working with children who had behavioral disorders and learning disabilities. She then began nursing school and started looking for a volunteer EMT position on an ambulance. She eventually found that position with the Robertson Fire Department in north St. Louis County, and it turned into a full-time job.

“it was difficult finding a job as an EMT because at that time, the late 1970s, women were not doing – or allowed to do – that kind of work,” explains Ross. “I became the first woman in St. Louis city and county to enter the fire service.”

A firefighter/paramedic with the Maryland Heights (Mo.) Fire Protection District since 1982, several years ago Ross discovered another way of helping others in distress. As a volunteer with the Missouri Region C technical search and rescue team, canine division, Ross and her two dogs, Moses and Haley, help search for missing persons, alive and deceased – on land and in water – and assist police departments in locating evidence at crime scenes.

Ross was the ony canine team sent to the site of the late Missouri Gov. Mel Carnahan’s plan crash, and she was on call for deployment to Ground Zero.

“I became interested when a member of the canine search and rescue team brought his black Lab to a house we were demolishing in St. Peters, Mo.,” says Ross. “To help him demonstrate what his dog could do, I hid in the bathtub with debris and a mattress on top of me. I could hear the dog sniffing around. Then he caught my scent and began barking and trying to get under the mattress. I was so impressed I decided to become involved in canine search and rescue.”

Ross trains her dogs several times a month with the search and rescue team, and she travels weekly to Columbia, Mo., to participate in training that will lead to her dogs being certified by FEMA.

“Search and rescue can be difficult work, but it’s always a good feeling to know you’re helping someone who is lost or a family worried about a missing relative,” says Ross.